Conflicted Thoughts About Having Kids

a questionable adventure

I long assumed I would have kids. But five years ago, around age 36, I started having second thoughts.

Practically speaking, I wasn’t in a solid relationship with a woman who wanted kids. I ran travel programs that took me away for multiple months. I earned enough to support myself but probably not anyone else. I didn’t have a home or permanent living situation.

Yet these were not the main obstacles. If kids were the goal, I could have found a different kind of work, a family-oriented partner, and a home. All were real possibilities. Instead, I began looking at child-rearing differently.

Treacherous Waters

The first tremors arrived in 2018 when I researched the history of parenting culture for my book, Why Are You Still Sending Your Kids to School? I wanted to understand why so many parents are hesitant to give freedom and responsibility to their children, leading me to a treasure trove of history, psychology, and sociology about the phenomenon known as “intensive parenting,” the approach that began replacing the older, laissez-faire, “go play and be back by dinner” in the eighties and nineties.

The sociologist Sharon Hays describes intensive parenting as any approach that is “child-centered, expert-guided, emotionally absorbing, labor intensive, and financially expensive.” Another sociologist, Frank Furedi, uses the term “parental determinism,” indicating the belief that if your kid fails, it’s your fault, and if they succeed, it’s to your credit. The psychologist Alison Gopnik employs the analogy of the gardener and the carpenter: a gardener waters and nurtures her plants but does not imagine she might control how they grow, while a carpenter measures and cuts with absolute precision and control. The internal story of a carpenter parent goes like this: “If I can just find the right manual or the right secret handbook, I’m going to succeed at this task the same way that I succeeded in my classes or I succeeded at my job.” Risk-averse and micromanaging, intensive parenting is often parodied as helicopter, snowplow, or drone parenting. Once exclusive to the upper-middle class, it’s now the dominant approach in the United States.1

Learning about intensive parenting came as a shock but not a surprise: something I didn’t want to believe yet I immediately recognized as true. I realized that I was sheltered in my work with self-directed young people (through summer camps, travel trips, and outdoor programs) and their parents (for whom I spoke at alternative schools and homeschool conferences). I had ignored the whiffs of intensive parenting that arrived via media and interactions with more mainstream families. Now the picture was becoming clear: we are swimming in treacherous waters.

Why is this a problem? Can’t you just parent the way you want? Deeper reading alerted me to the reality that it’s actually really difficult to opt-out of mainstream parenting culture. It’s not just a personal choice; it comes at you from all angles. That’s why it’s called culture. Friends, family, media, institutions, law, and children’s peers all pressure parents into acting and thinking a certain way, especially on matters of safety and risk. The fact that I personally knew a handful of hip, liberated unschooling families suddenly didn’t feel so convincing—like arguing that since Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg dropped out of Harvard, you’ll probably become a billionaire if you do too. Assuming I even had a philosophically aligned co-parent, could we really raise children in our own fashion, boldly flouting the norms? I might say “yes” with confidence, but I’m also aware that moms, not dads, bear the harshest brunt of social judgement regarding child-rearing. Nor did I like the idea of removing myself from mainstream society to raise children in some isolated utopia, surrounded by people who look and think just like me.

A final concern: even in the coolest families I met, I mostly witnessed dads playing the backseat breadwinner role while moms drove the educational side of things. I fancied a role reversal: Blake, the stay-at-homeschool dad / writer / cook / crazy adventure dude, leading bands of neighborhood kids on spontaneous missions that would make John Taylor Gatto and Dev Carey proud. But where were these dads? Where, even, were the neighborhood kids? Parents seemed so busy working, and kids so isolated and scheduled. Novel parenting arrangements and Captain Fantastic-style weirdness felt so rare. Whatever this “intensive parenting” thing was, it seemed to suck all the oxygen out of the room.

Self-Absorption

Now it’s 2019. I’m still assuming that if I can tackle the culture problem, I might make a good parent. Then I encounter another powerful set of writing, one that shakes me to the core: Meghan Daum’s Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids. (If you’re thinking to yourself, “Blake, maybe you read too much,” I will address that later.)

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed is an anthology of professional writers, 13 women and 3 men, explaining their choice to go child-free in vulnerable and often devastating detail. Though it’s not a representative sample of adults, I felt very seen by the fact that every voice is (1) a serious writer (2) who loves ideas and (3) needs lots of personal space. Because as much as I adore travel, dance, summer camps, and other kinds of hustle-bustle, I’ve always seen myself first as a reader, writer, lover of ideas, and someone who needs lots of space and time to do his own thing.

Check out my favorite quotes from Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed. It’s an astounding collection of observations and arguments. Here’s what stood out:

the loneliness and boredom involved with caring for small children

how, between parents, conversation relentlessly gravitates towards practical topics of child-rearing rather than stimulating, bigger-picture topics

the need to sustain a reliably high income to afford childcare and extracurricular activities

the near-impossibility of large blocks of quiet, undisturbed time if you insist on being part of your child’s day-to-day life

the high probability of life becoming a stressful rushing from one place to another

the perceived obligation to immediately respond to a child’s every question, treat every thought as a special contribution, and accept frequent interruption to adult conversation

the deeply positive and meaningful role one can play as an alloparent (a non-biological parent figure)

the possibility of, rather than raising my own children, serving as a role model to my friends’ children, demonstrating how an adult might live a different, interesting, unconventional kind of life

the remote but real possibility of resenting my child for “destroying” my former life

You see the pattern. I fear loneliness, boredom, constant interruption, and intellectual atrophy. I’m scared of the prospect of major financial obligations, the resulting stress, and the detrimental effects to my personality, optimism, and joie de vivre—all of which I consider my best credentials for becoming a parent in the first place.

Regarding the final point about resentment, I will share one excerpt from the anthology in its entirety, written by Sigrid Nunez:

Who knows. If I’d gone ahead and had a child, maybe what happened to Natalia Ginzburg would also have happened to me. I would have begun to feel contempt for writing, my bundle of joy replacing it as the most important thing. This is not impossible for me to imagine. But the picture that comes far more readily to mind is one in which I am typing with one hand and batting a toddler away with the other. And how would I have felt in that situation? I know exactly how I would have felt: angry, frustrated, burning with resentment toward the child, and no doubt toward its father, too. Full of self-loathing, tormented with guilt for having made my child the adversary to my vocation. And if there is one thing I am certain would have destroyed me, it is this conflict.

Is it selfish, shallow, and self-absorbed to want to avoid a likely case of self-destruction and self-loathing?

The book’s title is tongue-in-cheek, but I do think the term “self-absorbed” suits me. I am self-absorbed! I spend a lot of time in my own head, and I like it that way. I have a very good relationship with myself. To displace that relationship for multiple years seems dangerous at a minimum, and catastrophic at a maximum.

Having children is a classic example of what philosopher L.A. Paul calls a transformative experience: a decision that transforms you as you experience it. Sort of like becoming a vampire:

Because a person would be fundamentally transformed by becoming a vampire, they cannot possibly know in advance what being a vampire is like. Other vampires might offer information, but their advice is likely shaped by their own irreversible choice. In this situation, a fully informed comparison of preferences and values is impossible.

Rational choice theory works well for choosing a new laptop, a college major, or a new job. These are reversible decisions. But if you take the role of parent seriously, it’s not reversible. It’s one-way. Some level of self-annihilation is required.

Each of the contributors to Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed acknowledge this epistemic reality. They recognize that they’ll never know for sure what being a parent will be like, yet they remain confident in their decisions. Many are in their sixties now. They walked away from the promise of an ineffable experience, not from fear or ignorance, but with the clear-eyed knowledge their decision may cause more harm than good.

For me to remain my current self would mean continuing my footloose travel, my undisturbed writing and unbroken conversations, my low-pressure entrepreneurial experimenting, and building relationships with both adults and young people on my own terms. If that’s self-absorption, it sounds pretty great. But becoming a vampire—err, I mean parent!—might also be great. Who knows? As Cheryl Strayed once wrote to a 41-year-old man in a similar situation:

I’ll never know and neither will you of the life you don’t choose. We’ll only know that whatever that sister life was, it was important and beautiful and not ours. It was the ghost ship that didn’t carry us. There’s nothing to do but salute it from the shore.

Not Wanting to Bring a Child into this World

I’m being deliberately misleading. Because unlike some millennials, I don’t worry about climate change rendering our world uninhabitable in the near future. Nor am I antinatalist. I think more people will probably create a better world, in fact.

But I do worry about phones.

As social psychologist Jonathan Haidt has long warned, smartphones and social media are likely connected to rising adolescent anxiety, depression, and self-harm. In my work with teens, his thesis rings true.

Of course, we adults are just as bad. We are on our devices all the time! We scroll while watching movies, we message in the middle of conversations, we take our phones to bed, and we give them more attention than friends and loved ones.

Last month I penned a poem while sitting in a café in Patagonia where every single person was glued to their phone. No one talked to each other. I couldn’t help it.

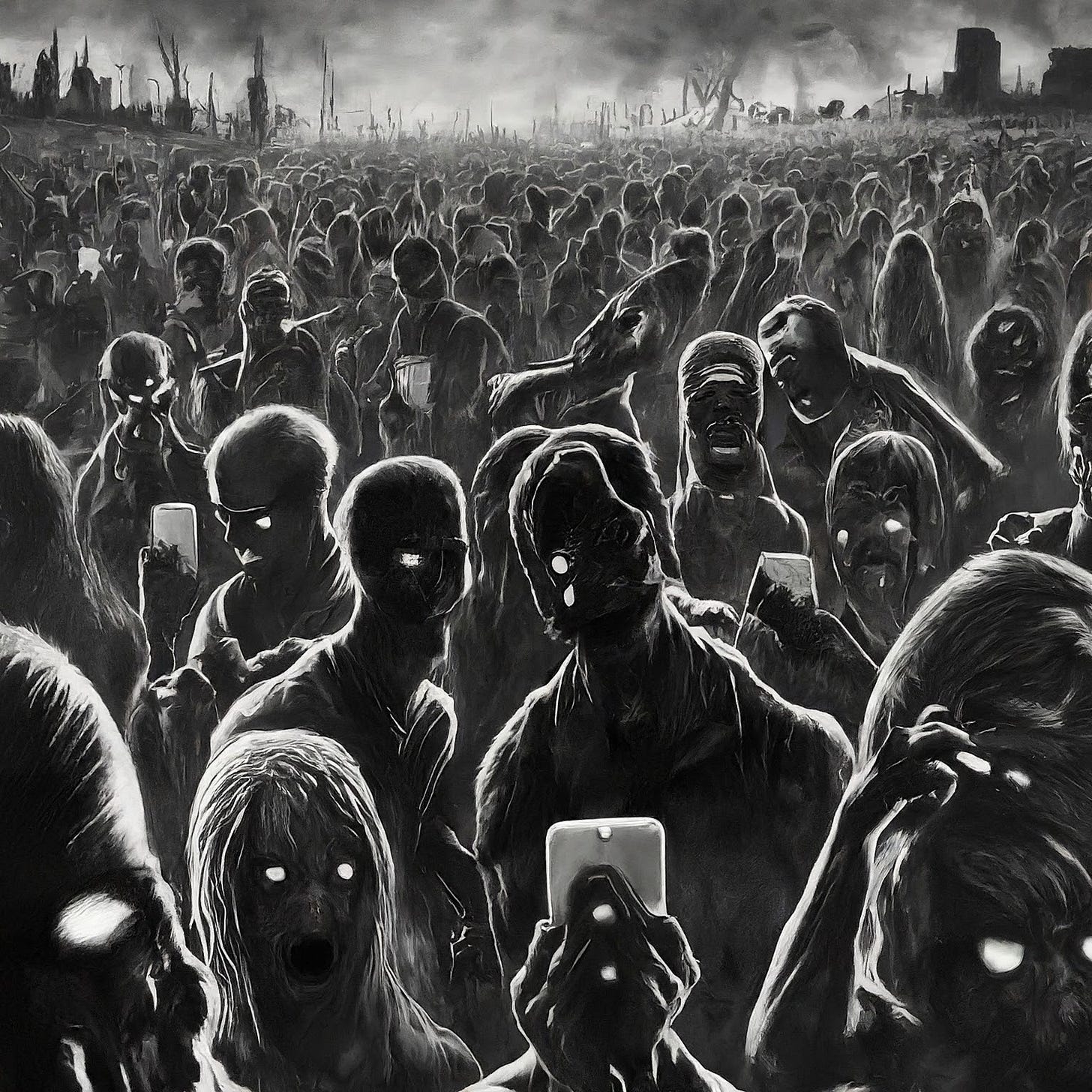

You are hunched over, dead-eyed

Slack-jawed, in slow decay

Spine curved, neck tilted

You don’t move, you twitch

Surrounded by your fellows

Each lost in their own worlds

Mesmerized by flashing lights

The scent of blood on the ground

You hunger ravenously

You are never satiated

A former human body

Reduced to thumbs, fingers, eyeballs

You scan the horizon

For signs of life

Seeing only other zombies, you conclude

This is life

Now this is a world I fear bringing a child into.

Specifically, I fear inhabiting a big modern house (i.e. private castle) where family members hide in their rooms with their phones, tablets, and laptops, instead of participating in even a semblance of communitarian life. I imagine getting 30 minutes of dinner discussion time before everyone retreats to their respective domains, myself included. If first-time parents fear sleepless nights and the constant interruption of early childhood (ages 0-4), then this is my fear of later childhood (ages 9-18).

In my life as a permanent traveler and frequent houseguest, I relish the attention that I give and receive during a short stay. It feels like we’re really caring for each other, like we’re really present. I imagine that this care and presence is what many of us hope a family will guarantee. And I bet that life with young children is like this: they are a captive, adoring audience. But when it comes to older children and technology, I lose confidence.

Easy solution—why not just restrict devices? As Jonathan Haidt preaches, “no smartphones before high school!”

As with parenting, the culture of technology is very tricky to escape. When a child feels genuinely excluded from their peers because they lack the tools to participate, that pain is really difficult for a parent to ignore. As Haidt points out, changing technology norms is a collective action problem. Maybe don’t bet on that one.

I also have a long-standing philosophical conviction against restricting technology. Instead of banning something, I believe in offering something better. Kids aren’t glued to devices just because they’re “addictive” (i.e. effective). They’re glued because they enjoy so few meaningful options for otherwise spending their time. If you grew up isolated in suburbia, I bet you’d love TikTok, too.

On my recent cycle trip in Patagonia, taking a rest day in Cholila, Argentina (the same town where Butch Cassidy hid from authorities), I met a French-Canadian dad traveling on horseback through the Andes with his 13-year-old daughter for multiple months. The daughter participated in mounting, grooming, feeding, and watering the horses. She packed and unpacked the saddlebags. Over two days, I did witness the daughter on her phone at times. But she clearly enjoyed working with the horses and helping with practical tasks like grocery shopping. This young woman was on an adventure. She had purpose. She was doing something so much more interesting, real, and consequential than a phone could offer.

This, it seems, is how you win the zombie war.

Maybe you’re thinking: “There you go, Blake. You found your model. Why not become like horse dad?” Well, maybe. I didn’t inquire into horse dad’s marital status. I got the feeling he was divorced. What an understanding ex he must have! Or perhaps he was running from the law like Butch Cassidy.

In all seriousness, I’m not sure what to do with examples like horse dad. Is it reasonable to assume I can muster all the factors necessary to do something like this: supportive partner + financial resources + opportunity + health + willing child? I haven’t even touched on the most uncontrollable factors that might shape a parent’s journey: how the pregnancy goes, unforeseen illness and disabilities, genetic disorders, etc. My dreams are just one part of this big ol’ equation.

I’m left with more questions than answers. How strong is the gravitational pull of culture? How far can we bend the rules? How important is it to stand by one’s philosophical convictions? Am I just lamenting technology’s grasp like every other oldie? Does every generation have its own version of “not wanting to bring a child into this world?”

Overthinking it

Finally, I’ll just say it: I’m really overthinking things, aren’t I?

Do I read a lot of books and articles? Do I spend a lot of time in my head? Do I worry about controlling things that can’t be controlled? Did most humans before me just have kids and figure things out as they went along?

Yes, yes, yes, and yes. Yet here we are.

Perhaps this post reveals the deeply imbedded nature of intensive parenting. Look at me! I’m so concerned about not messing up prospective parenthood. I read, I study, I worry, I want to get it right. Just like Alison Gopnik predicted, I’m a 1980s baby who never had to care for siblings or young children, but I do have lot of experience with school and jobs, so it’s natural for me to “conceive of child-rearing as another goal to be tackled with the same ferocity as [my] first professional appointment.” Look at this giant pro-and-con list I’ve composed! It’s actually more a con list, since the pro side seems so well defined. I’m 41. How long might I continue analyzing before I officially enter dinosaur territory, and doing something like a multi-month Andean horseback trip with a 13-year-old is no longer possible?

I am the face of demographic decline.2

Practically speaking, here’s where I’m landing at the moment.

If I’m going to become a parent, I’d prefer to be in Europe—at least in the early years, with all the subsidized parental leave and childcare and such. In Europe, free-range childhoods still feel possible. The urban density, public transport, parks and playgrounds and other parental amenities feel like a strong hedge against isolation. Perhaps around age five, when anti-homeschooling laws kick in, I’ll want to ditch for foreign shores. But that’s a bridge to cross later.

If I’m going to become a dad, I want to do it alongside an amazing partner. Someone who wants to bend the rules, who possesses a flexible livelihood, who is already expressing her unique freedom in this world. Someone with whom I’m sufficiently philosophically aligned that, should we separate, I’m confident she would be a positive influence in my child’s life.

Otherwise, I don’t think I’ll try to have my own children. I will doggedly pursue my unique vision of growing old, free to follow my weirdest and wildest individuality. I can still play a role in the lives of children—as an educator, alloparent, godparent, stepparent, or regular visitor—and perhaps help other parents feel less isolated in their own lives.

Every path sounds good. I’m definitely overthinking it. But that’s me.

Your thoughts, as always, are welcome.

[Follow-up article with crowdsourced responses]

Learn more about intensive parenting in this excerpt from my 2020 book, this 2018 article, and this recent podcast.

In case you missed the news, people all over the world are having fewer children, leading to a so-called “demographic crisis.” See this podcast and this article.

You're not wrong. I wouldn't trade my three for all the free time in the world, but it's surely my life's work. There are highs and lows, but the exhaustion seems to draw from its own well. Kid problems are annoying but manageable, teen problems are also annoying but more high stakes, and then they are grown and it's heart wrenching to see them struggle. So it doesn't get easier. But two nights ago, we were on a family group text on What's App....Florida, Buenos Aires, Whitefish, and North Carolina, and I have never, on my honor, laughed so hard for so long. We were all literally rolling on the floor at our own weird brand of humor. My daughters room mates checked on her because she was screaming with laughter. And it occurred to me that I've raised a little tribe of folks that are sympathetically and soulfully wired to love each other through the highs and the lows of this crazy life. Which is pretty cool. My book probably won't get written and I will die poor...having given every red cent happily to those three kids, but what the heck?! If the opportunity knocks, in a quaint European village with a woman that sings your same tune, I'd say throw caution to the wind and fall head first down the parenting pit. Or not! On another note, but somewhat similar....I think you might love to read the book that I just finished. It's called 'My Half Orange' by John Julius Reel, and he did exactly what you speak of...married a beautiful Sevilliana who danced into his heart a bit later in life and then two kids sort of magically appeared. It's self published and so good! It's also about learning Spanish. He was my daughters professor in Spain and she just loved him. Check it out! Also reading Kenneth Danford's book and loving it...thanks so much for that connection! I have a meeting with his daughter this week!

It's certainly a tough nut to crack. As a full-time homeschooling dad of two kids who came to parenting late in life (in my forties), I guess I would just say: a) parenting tends to find you whether you planned for it or not, whether it's your kids or not, b) you don't need to fit into a conventional, or even a non-conventional, mold of parenting any more than you're conventional in any other area of your life, and c) for what it's worth, what seems like giving up parts of yourself from one perspective can actually be quite a relieving liberation from always being trapped in your own inner world. You'll evolve and grow no matter which way it goes.

If you ever want to talk about it, reach out!