The Privilege of Wandering Europe

on the origins of our wealth

Last November, I met a blonde and bright-eyed German woman at a fusion dance in Berlin.

“What are you doing in Europe?” she asked.

“Traveling around, visiting friends, going to dances,” I said.

“What do you do for work?”

“I work for myself.”

“Oh, did you just exit?” (Implying: Did you just sell your company?)

I blushed. She thought I was a startup founder! Perhaps one who just pocketed a few million dollars and was now touring Europe.

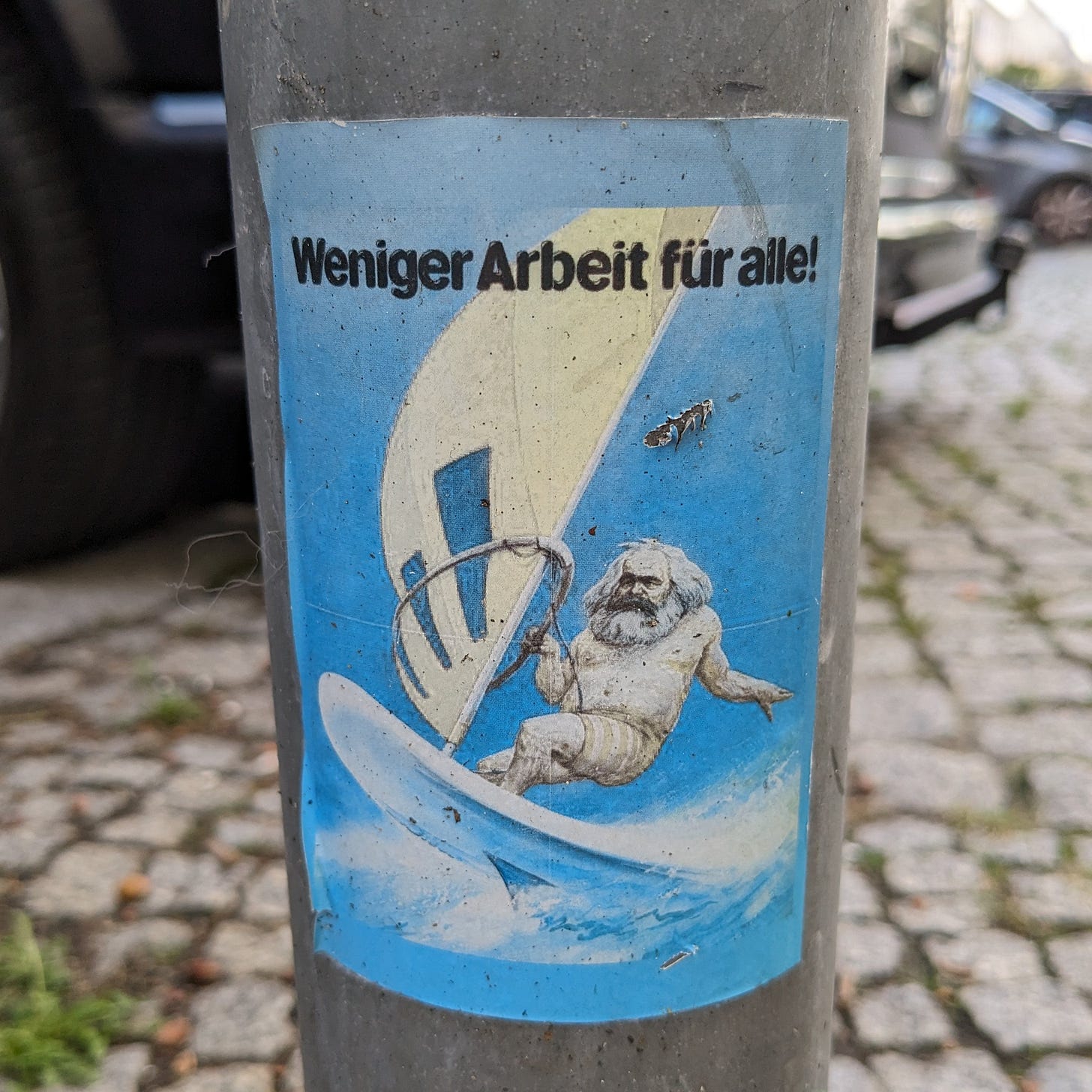

“No,” I laughed. “I do work. Just not too much.”

We continued chatting between dances. She told me that she was planning to launch her own startup—while finishing her Ph.D.—in the university town of Jena, a few hours south of Berlin.

“Hey, I just started reading a book about Jena!”

I was referring to Andrea Wulf’s book, Magnificent Rebels: The First Romantics and the Invention of the Self, which I’d recently found in a Berlin bookstore. It chronicles the drama-soaked lives of a handful of German philosophers in Jena at the end of the 18th century, the founders of what we now call “romanticism.”

Rebelling against the impersonal, reason-driven values of the Enlightenment, the Jena set championed the human emotional experience and the importance of authenticity, awe, and connection to nature. Their ideas would later infect the English poet-philosophers (like Wordsworth and Coleridge), who in turn inspired the New England transcendentalists (like Emerson and Thoreau), who would ultimately nurture the 20th-century American counterculture (like Kerouac) that radically shaped my young adulthood.

Two centuries later and here I was, meeting someone from the same German university town that planted the seeds of my desire for ecstasy, transcendance, and adventure.

But that’s not what I was thinking when I met the blonde dancer in Berlin.

Rather: “Isn’t it funny that she assumes I’m rich?”

It makes sense. The average American adult on vacation in Europe might spend a few thousand dollars in one week. Who, if not the wealthy, can afford to travel around Europe for months on end—dancing, visiting friends, and not working too much?

In Magnificent Rebels, Andrea Wulf describes a traveler who briefly entered the life of the book’s heroine, Dorothea von Schlegel. He was:

an aristocratic adventurer from Italy who had been brought up in a monastery and who was wandering across Europe in search of love, friendship and freedom. . . .[He] had stopped in Berlin on a whirlwind tour through Europe. Peripatetic, independent and in search of freedom, the young man had not stayed for long and their affair had been brief.

Wandering Europe in search of love, friendship, and freedom… hey, that sounds like me! Except that I’m from the suburbs of California, and I’m no aristocrat.

Back in the 1700s, aristocrats were the only ones who could afford to do a European Grand Tour. But over the next few hundred years, such travel became increasingly possible for middle-class professionals and small-scale entrepreneurs like myself: those who work, save, and pay their own way, rather than depending on substantial financial support from families.

I am undoubtedly historically rich. I am dirtbag rich. But I am not old-money rich, tech-bro rich, or White Lotus rich. Yet I can still choose to wander around Europe in search of love, friendship, freedom, and fusion dance.

Isn’t this fascinating? How is this even possible?

One of my favorite questions to ask fellow international travelers is this:

How can you afford to travel the world, while so many others cannot?

Let’s say you’re Swiss, Danish, or Kiwi. Your average income is very high. Your living costs are high, too, but with determination and thrift, you can save up a small pile of money. And this money will allow you to travel in many other parts of the world (like South America, where I happen to be right now) for a very long time.

Yet the average citizen of a South American country, working just as hard as you, in the same kind of job, with equal thriftiness, will save only enough money to travel in Switzerland, Denmark, or New Zealand for a very brief time, if at all. The plane tickets alone might be out of reach.

Why is this? Forget visa restrictions for a moment. Just focus on purchasing power. Assuming you’re from North America, Europe, or a handful of other rich countries, why does one unit of your effort purchase so many goods and services in South America, whereas the same unit of effort by a South American purchases less in your home country?

Let’s just say that this question makes people… uncomfortable. It feels like a question of privilege, unearned and unjust. It’s a question for which few of us have a good answer. How did your country get so rich?

On the Unschool Adventures trip to Mexico in 2022, I proposed a variant of this question to some of the teenagers, legs dangling in a hostel pool on the Oaxaca coast:

Why does a taxi driver in San Diego (California) earn so much more than an equally talented taxi driver who lives just across the border in Tijuana (Mexico)?

Again, we’re talking about real, cost-of-living-adjusted purchasing power. The driver in San Diego who works and saves for a year can take a much longer vacation in Mexico than the equally industrious Mexican driver can take in San Diego.

The best answer my group could muster was “the legacy of colonialism.” Most admitted they had no idea. This aligned with the responses I received for many years from the international traveler crowd: either some version of “rich countries exploit poor countries” or “no clue.”

How fascinating! We citizens of rich countries are the unwitting beneficiaries of a series of historical circumstances that conspired to increase our material purchasing power. Yet this increase can’t only be explained by exploitation, because since 1800, everyone’s real purchasing power has increased. Anyone with a fixed-pie concept of economics—in which one group can only prosper by immiserating another—will struggle to explain this phenomenon.

Back in the time of the Jena philosophers, almost everyone was dirt poor. Even aristocrats pooped in chamber pots and perished from now-eradicated diseases. But today, materially speaking, virtually everyone is better off. The mere fact that a thrifty taxi driver from Tijuana might take a vacation—if only within Mexico or neighboring Guatemala—is an unprecedented event. Across history, most people could not even contemplate traveling for pleasure. You were born somewhere, you stayed there, and you didn’t wander far. Now middle-class adventure-seekers like myself wander the globe like a swarm of faux-aristocrats.

Do I ever feel guilty about my privilege relevant to my equally clever, thrifty, and hard-working foreign counterparts? Of course I do. But what good does this guilt accomplish if rooted in ignorance rather than nuance? Shouldn’t we privileged few attempt to understand the origins of our fortune rather than resorting to shrugs or simple morality tales? Shouldn’t we then use this knowledge to expand the envelope of privilege, allowing more people the option of wandering Europe, or South America, or anywhere—in search of love, friendship, and freedom?1

If you’re waiting for a big reveal—Blake answers all the hard questions of development economics!—sorry to disappoint. I remain a 🐌-paced self-directed learner in the realms of economic history and political theory. But if you’re curious where I’m coming from, I recommend beginning with Deirdre McCloskey’s eloquent, incisive, and entertaining 2020 book, Leave Me Alone and I’ll Make You Rich.

If I may venture one answer to your question, Blake, I think it in part has to do with the fact that some countries are materially richer than others (why that is is a whole other question, which I won't attempt to get into here). But if we take that as our starting point, then we can observe that in a richer countries, things cost more. This is because, with more money flowing around, the price of things gets bid up. And because things cost more, wages need to be higher, so that people have a chance of affording those more expensive things. Meanwhile, in materially poorer countries, with less money flowing around, things cost less. So someone from a rich country can make a bunch of money (though saving it can be a challenge when they have to pay for those more expensive things) and travel to a place where things cost less, and stretch their money much further.

That's one explanation I can think of. I'm sure there are others, like how the exchange rate between different currencies favours rich countries (because speculators want to buy currencies from rich countries, but not poor ones, which increases their relative value).

I'll stay away from the morality of all this; I just wanted to try to offer a practical explanation for what's going on.

Enjoying your newsletter!

Jared Diamond has been devisive in the subject of history; I think a great counterpoint (and one that shows how much prehistoric folks did actually travel) is The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow. Discusses economics, politics, agriculture, currency, credit, travel, etc. It’s a good long read. 11/10