Ecstasy, Transcendence, Adventure

on Losing Control and The Dharma Bums

MY EYES ARE CLOSED. My smile is wide. My arms are wrapped around her body.

Together, we move to the music: spinning, tilting, pushing, pulling, rolling, shaking, gliding, stepping, step-touching, dipping, pausing, breathing. Sometimes even twerking.

It is early January 2023, and we are in a large dance studio in Bern, Switzerland, for a 3-day partner dance event. It doesn’t matter who my specific partner is; I have many throughout the weekend. About a quarter of a time, she is a he. (Or: who knows, who cares?) Body shape, gender, attractiveness, dress—all irrelevant.

Instead, I pay attention to smile, warmth, enthusiasm, respect, responsiveness, and presence. Do we connect? Can we play? Can we drop our thinking, our worrying, our self-awareness? Can we obey the music and create something beautiful together for 3 minutes?

In other words: Can we transcend ourselves? Can we spark a moment of ecstasy?

Because that’s why I’m here. Not to look good. Not to master a technique. Not to meet somebody.

I’m here to lose myself.

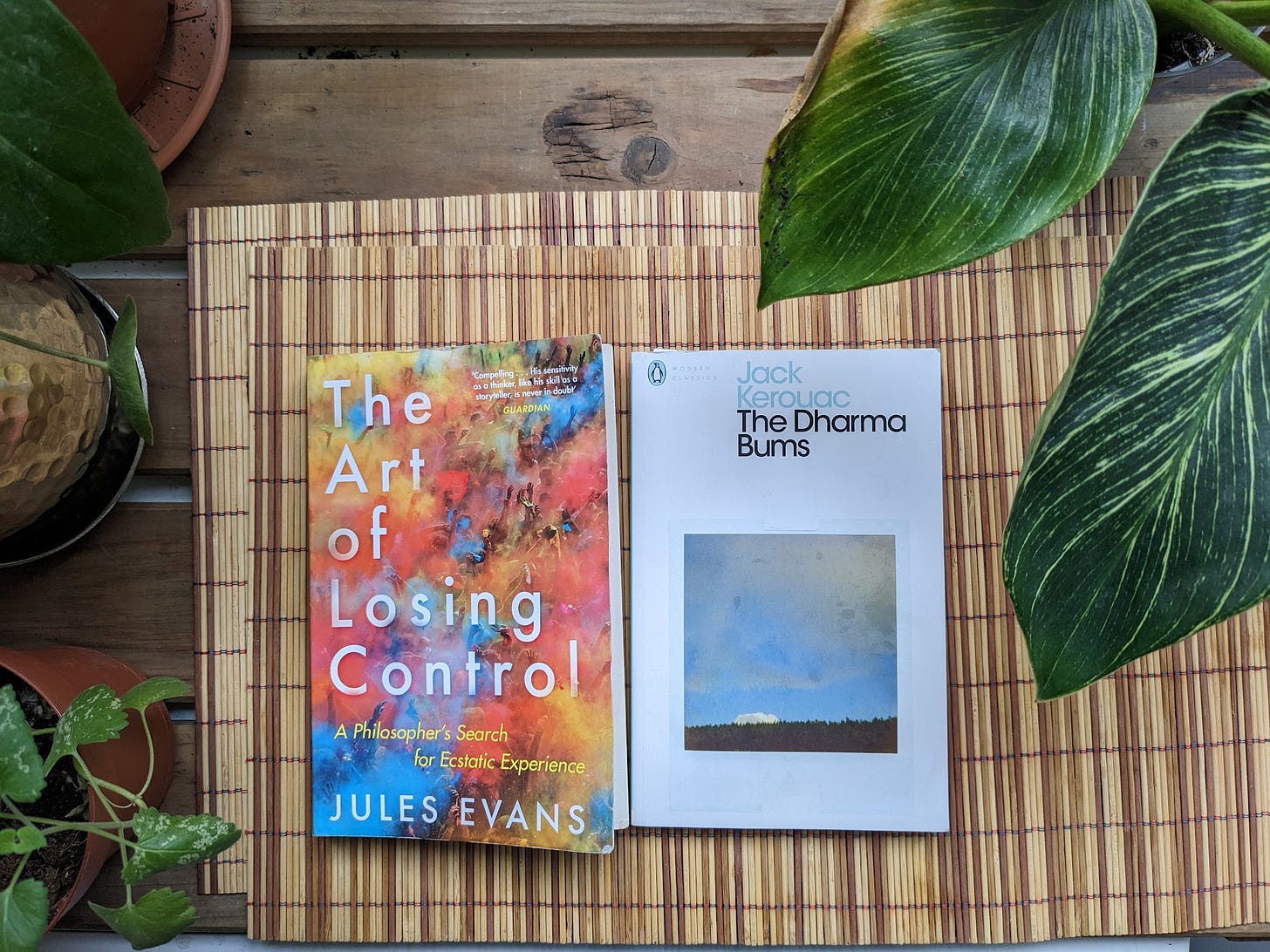

WHILE GALAVANTING around Europe last last year, I stumbled upon an eye-catching title in an Amsterdam bookstore: The Art of Losing Control: A Philosopher’s Search for Ecstatic Experience.

Well-researched and lucidly written, this book helped me connect the dots between various activities that have played important roles in my life—partner dance, endurance sports, extended time in nature, meditation, and large-group “hippy bonding activities”—by showing me how the pursuit of adventure is linked to states of ecstasy, transcendence, and “flow” that are otherwise absent from day-to-day life.

The author, Jules Evans, nicely summarizes the history of ecstatic experiences, the decline of traditional religions, and the 1960s resurgence of mystical pursuit:

Eastern contemplative practices, including Vipassana, yoga, tantra, Transcendental Meditation and Hare Krishna, were brought over to the West in the 1960s and attracted huge followings. New Age spirituality flourished through Wicca, magic, neo-shamanism, nature-worship and human potential encounter sessions. Psychedelic drugs became widely available. The sexual revolution encouraged people to search for the ultimate orgasm at swinger parties and leather clubs. People sought immersive experiences at art-happenings, experimental theatre and underground cinema. Rock and roll took Pentecostal ecstasy from black churches, secularised it, and brought it to white middle-class audiences. Even sport became a means to transcendence - people turned to surfing, mountain-climbing and jogging as a way to get out of their heads. There was a widespread urge to lose control, turn off the mind, find your authentic self, seek intense experiences.

In a 1962 Gallup poll, 22% of Americans declared they’d had a “religious or mystical experience.” By 2009, it was 49%. The counterculture of the 60s & 70s brought transcendent experiences to an increasing number of Westerners through massive concerts and dance parties, fine arts (cinema, theater, literature, poetry), mind-altering substances, mindfulness practices, and wilderness immersion. But the it wasn’t all roses:

Baby-boomers' enthusiastic search for ecstasy led to some dark places. Seekers ended up in toxic cults. Charismatic Christianity became associated with huckster mega-churches and the intolerant politics of the religious right. Eastern gurus turned out to have clay feet. The New Age embraced all kinds of nonsense, from horoscopes to crystal skulls. LSD turned out to be less benign than its prophets had predicted—people lost their minds, ended up in psychiatric institutions. The free-love revolution climaxed in an epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases.

Evans shines a light on the ecstasy found in violence, team sports, and nationalist politics—and why we’re unlikely to wish it away. Without effective outlets for these kinds of feelings, he writes,

…life feels boring, depressing, atomised and meaningless. . . [The] 'war within' can lead to a permanent 'inner unrest', compulsions, addictions, depressions, anxieties and a constant sense of the artificiality and immorality of the civilisation in which we live.

Escaping the perceived artificiality and immorality of the modern world clearly “pushes” many of us toward adventure. There also significant “pull” forces, such as extended time in nature:

While absorbed in nature, we drink from the 'quiet stream of self-forgetfulness' . . . The rhythmic activity of strenuous walking (or riding, or fell-running, or wild swimming) lulls our mind and takes us into a state of reverie, in which we can commune with external nature and also with the inner nature of the subliminal mind.

Reading The Art of Losing Control was a delight in itself. But it also helped me to reexamine another book I stumbled upon in a different European bookstore—one that played a powerful role in my young adulthood—The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac.

WHEN MY BEST FRIEND handed me a copy of On The Road at age 17, I was compelled by Jack Kerouac’s unabashed pursuit of wild experiences in stolid 1950s America and his lyrical “spontaneous prose.” But I was also repelled by the constant drinking and drug binges, the female objectification, and the frenetic (and often criminal) antics of Neal Cassady, the book’s hero.

It was The Dharma Bums, Kerouac’s lesser-known 1958 novel, that stole my heart in college. Taking place after the events of On the Road but before Kerouac’s meteoric rise and subsequent alcoholic descent, The Dharma Bums celebrates a far more innocent and honorable character: the 25-year-old poet and East Asian scholar Gary Snyder. The book still offers a cringe-worthy dose of boozing and womanizing, but that is outweighed by Kerouac’s honest investigations into Buddhism, his masterful descriptions of Snyder, and one highly memorable camping/climbing trip in the California High Sierra.1

Framed in Berkeley and Marin County (where I went to college and spent my youngest years, respectively) and projecting a highly romantic vision of eastern spirituality, spontaneous travel, poetic playfulness, and wilderness retreat in the California High Sierra (with which I was already falling in love), I now see that 19-year-old Blake was primed to embrace The Dharma Bums. And embrace it I did.

While I empathize with much of Kerouac’s personal journey in the book, it was his description of Gary Snyder that most firmly captured me.

I saw Japhy [Gary Snyder] loping along in that curious long stride of the mountain-climber, with a small knapsack on his back filled with books and toothbrushes and whatnot . . . He was wiry, suntanned, vigorous, open, all howdies and glad talk and even yelling hello to bums on the street and when asked a question answered right off the bat from the top or bottom of his mind I don’t know which and always in a sprightly sparkling kind of way. . . Japhy was in rough workingman’s clothes he’d bought secondhand in Goodwill stories to serve him on mountain climbs and hikes and for sitting in the open at night, for campfires, for hitchhiking up and down the Coast.

In Snyder, Kerouac saw a modern saint who embodied the virtues of voluntary poverty, connection to nature, and countercultural authenticity:

[he] was considered an eccentric around the campus, which is the usual thing for campuses and college people to think whenever a real man appears on the scene—colleges being nothing but grooming schools for the middle-class non-identity which usually finds its perfect expression on the outskirts of the campus in rows of well-to-do houses with lawns and television sets in each living room with everybody looking at the same thing and thinking the same thing at the same time while the Japhies of the world go prowling in the wilderness to hear the voice crying in the wilderness, to find the ecstasy of the stars, to find the dark mysterious secret of the origin of faceless wonderless crapulous civilization.

Exploring their shared love of Buddhism and dirtbag culture, Kerouac and Snyder predicted a new social movement of “Dharma Bums” and “Zen Lunatics” wandering around the the USA in pursuit of bliss, ecstasy, solitude, and altruism:

[A] great rucksack revolution thousands or even millions of young Americans wandering around with rucksacks, going up to mountains to pray, making children laugh and old men glad, making young girls happy and old girls happier, all of 'em Zen Lunatics who go about writing poems that happen to appear in their heads for no reason and also by being kind and also by strange unexpected acts keep giving visions of eternal freedom to everybody and to all living creatures…

And they weren’t far off! Kerouac anticipated many significant values of the 60s—minimalism, optimism, innocence, and adventure—and wrapped them all into his idealized description of Snyder:

This poor kid ten years younger than I am [Gary Snyder] is making me look like a fool forgetting all the ideals and joys I knew before, in my recent years of drinking and disappointment, what does he care if he hasn’t got any money: he doesn’t need any money, all he needs is his rucksack with those little plastic bags of dried food and good pair of shoes and off he goes and enjoys the privileges of a millionaire in surroundings like this. And what gouty millionaire could get up this rock anyway?

If you were a mild-mannered California suburban kid dropped into the heart of Berkeley—one who was already questioning consumerism, already open to Eastern spirituality, and already lusting for authentic travel—what better role model could you find?

Kerouac spoke to me in a way that no one else could, advertising a playful, poetic, and self-sufficient mode of existence that embraced both wilderness solitude and wild city life. The Dharma Bums described a truly avant garde moment in American culture when a small group of west-coast artists, writers, scholars, and lunatics were fomenting a countercultural revolution. At the core of the Beat movement was “beatitude”—which means blessedness, bliss, ecstasy, heavenly joy—and that, I knew, was for me.

Happy. Just in my swim shorts, barefooted, wild-haired, in the red fire dark, singing, swigging wine, spitting, jumping, running—that's the way to live.

FROM CHILDHOOD through age 18, my life was very much “in control.” While my family split up early and I ended up living in many different households, each was stable and loving. I played the school game well, I regulated my emotions well, and I didn’t take big risks.

Moving to Berkeley at 19, independent and empowered, I now felt ready to relinquish some of that control in exchange for ecstasy, transcendance, and adventure. The Dharma Bums appeared at the right moment, and living in the countercultural student cooperative houses only fueled the fire. Other books opened my eyes to other forms of ecstatic pursuit. I spent my summers in a wilderness retreat surrounded by mountain bliss, prompting me to discover another camp that would help me fall in love with tango, which brought me to fusion dance—which, apparently, is how I ended up blissed out with a hundred strangers in Switzerland a few weeks ago.

My young adulthood, I see ever more clearly, was a rich tapestry of people, books, and organizations that honored the countercultural pursuit of ecstasy, adventure, and transcendence over stability, conformity, and service.

Has this all been healthy? Has it “worked out?” Are these values sustainable? What is even being “sustained?” These are questions to which I don’t yet have answers, and perhaps answers are not possible.

Notes on Adventure continues as my public forum for investigating the appeal of “adventure” and why people like me pursue adventure so doggedly, often to the exclusion of marriage, kids, house, and financial comfort. I’ve been writing this series for almost a year now, and I appreciate you following along—especially as I pen meandering, exploratory pieces like this one.

Your comments, public and private, are always appreciated.

♥️ Blake

Thanks for writing this, Blake! So well crafted and true.