Why Work When You Can Hike, Climb, Surf, or Ski?

a dirtbag rich teaser

If you desperately love moving your body swiftly through nature—hiking, running, climbing, cycling, surfing, skiing, slacklining, whatever it may be—then you are trapped within a contradiction.

To earn the money necessary to do these things, you must work. Yet work often means sitting indoors, staring at a computer: the slow death of the body in your most physically capable years.

What if this weren’t true? What if you could spend a majority of your time in nature, moving your body, doing that which brings you joy—while still supporting yourself financially and making a meaningful contribution to humanity?

Let’s explore.

We’re all richer, yet we’re still busy

In 1930, the economist John Maynard Keynes famously prophesied that 100 years later—approximately right now—the average citizen of a rich country (like his United Kingdom) would be eight times wealthier than one living today, working just 15 hours a week to cover the basics.

Keynes was right, and Keynes was wrong.

Most of us in rich countries today are much better off (materially speaking) than he assumed. Yet most of us still work 40+ hours a week.

How did this happen? How could we become vastly more wealthy than before and yet still find ourselves working just as much?

One reason is that the “basics” now include modern healthcare (see: hospitals in 1930), modern housing (see: construction in 1930), modern transport (see: long journeys in 1930), and modern consumption (see: food and entertainment in 1930).

Once the basics expand, it’s almost impossible to go back. In rich countries today, you can’t choose to live in a 1930s-quality dwelling or receive 1930s-quality healthcare. (You probably can’t even use a cell phone made a decade ago.)

If you drastically reduced your standard of living while continuing to earn a modern wage, 15 hours a week would be more than enough. But that’s called “living in squalor,” and we’ve outlawed it.

As a society gets materially richer, it drags its members forward in the name of human dignity. This is called progress, and it’s a rather good party. Many people die every day—crossing deserts on foot and oceans by raft—to join the progress party.1

If you live somewhere that other people are willing to die to join, you should consider yourself lucky. But that doesn’t mean you have to party the same way as everyone else.

Keynes recognized that material progress led to new possibilities for living:

Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.

The strenuous purposeful money-makers may carry all of us along with them into the lap of economic abundance. But it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.

— “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” (1930)

Here’s what I believe: Keynes was more right than wrong.

You can live well today—shockingly well—on 15 hours a week of paid work. And this can be good, satisfying work. Work that doesn’t immiserate yourself or others. Work that serves both yourself and your fellow human beings.

You can join the progress party just long enough to shake a few hands, kiss a few babies, snag some hors d’oeuvres, and then ghost—disappearing into the night to sleep under a blanket of stars.

Enter the dirtbag

The first dirtbags were hardcore rock climbers in Yosemite Valley in the 1960s who camped illegally, showered infrequently, and scavenged for meals. When they needed money, they’d leave the Valley to paint houses, wait tables, teach skiing, or even take a desk job: anything to refill their coffers and get back to the big walls. They lived like bums in pursuit of the good life.

Today dirtbags come in many flavors, not just “climber” and “white male.” Some are trail runners, mountain bikers, long-distance hikers, backcountry skiers, cross-country cyclists, or endless-summer surfers. Others are dancers, slackliners, or perpetual travelers. All are passionate. All are extreme. None are what the mainstream would describe as “balanced.”

Some dirtbags live in vans, trucks, or tents. Others couchsurf, hitchhike, or stay with friends. Some do pay rent: just not very much, and not for very long. For dirtbags, full-time, full-price rental contracts lie somewhere between a luxury and an obscenity.

Many dirtbags come from middle-class security. Some come from upper-class privilege. Others come from next to nothing.

All dirtbags revere nature, movement, and thrift. All struggle to fit into conventional society. All want to be left alone to do what they love, while they also yearn for membership in a tight-knit community of the similarly obsessed.

Many who lead such lives aren’t aware of the label “dirtbag.” Of those who are aware, many don’t welcome its associations. I understand their aversion, but I like the term.

To me, being a dirtbag simply means that you’re too busy following your bliss to worry about a little dirt under your nails. It means you’re doing something right.

Dirtbagging is unsustainable, as is normal life

Unfortunately, dirtbagging is unsustainable in the long run.

Traveling, adventuring, and living close to nature is undoubtedly fun and fulfilling—until you get seriously ill or injured, need to sleep or eat better, require comprehensive health insurance, want to save for retirement, get fed up with your menial seasonal jobs, fall in love with someone who’s not a dirtbag, or start a family. Normal life and its promise of security begin to look awfully attractive when the wheels come off your vehicle or finding shelter becomes a real issue.

Unfortunately, for people like me (and perhaps you), normal life is also unsustainable in the long run.

If dirtbagging calls to you, then attempting to live normally is a brutal reminder of why you cannot accept the full-time job, the boss, the commute, the meetings, the bureaucracy, the accumulation of junk, the normalization of debt, and the never-ending postponing of life.

Your body rebels against all the sitting: at desks, in cars, on trains. Your mind rejects the barrage of advertisements and entertainments, the chorus of phones buzzing and vibrating, the endless splitting of attention. Even among friends and romantic partners, you feel isolated and alienated.

You might fit in, but you know you’re out of place. You sense that something vital is being eroded, precious possibilities are being erased, and that you are growing old at an unacceptably early age.

Despite a growing bank account, you feel neither wealthy nor secure. You feel like a fraud.

A glorious compromise: becoming dirtbag rich

Fortunately, there is a middle way between conventional existence and hardcore dirtbagging: a path I call dirtbag rich2, which I currently define this way:

a high-freedom, low-income lifestyle

filled with nature, movement, and connection

fueled by purposeful, well-paid, part-time work

In the 15+ years since I decided to pursue this path, I’ve learned much about what it takes to become dirtbag rich. I’ve tweaked, refined, and pressure-tested my ideas in the mountains of New Zealand, on the highways of North America, and among the capital cities of Europe.

Your version of “dirtbag rich” won’t exactly match mine. We have different histories, personalities, aptitudes, and blind spots. What “purposeful” means to you differs for me, and that’s okay. What matters are the fundamentals:

working just 15 hours/week (averaged over the year) doing something that doesn’t hurt the world (and ideally improves it)

keeping your expenses dirt-cheap (without exploiting family or government) while gradually increasing your savings

spending lots of time doing what you love (often in the outdoors), alongside people you love

with time leftover for creative expression, entrepreneurial experiments, travel, romance, reading, friendship, and reflection

If this sounds idealistic, that’s because it is. Dirtbag rich is an ideal. But some people do live this way today; I’ve interviewed 38 of them so far. And why trash idealism?

As Keynes wrote a century ago, it will be those “who can keep alive” and “not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.”

The dirtbag rich don’t actually want to sleep in the dirt—at least, not against their will—and they certainly want to enjoy the riches that “science and compound interest” (and political activism) have won for them over time. Yet dirtbag rich is just one path toward a more humane future: a path particularly suited for those who must move their bodies through nature, frequently and intensively, in order to feel sane.

For people like us, retirement is a cult. We will not wait until 65 to do what we love, after our bodies have been compromised by decades of neglect. Vacations and weekends are not enough. We must find a way to live differently, now, before we self-destruct.

Many challenges remain:

How does one afford housing, eat decently, cover healthcare, and possibly care for dependents, without working full-time?

How does a low-income life mesh with the expectations of family and higher-earning friends?

Where, exactly, does one find these mythical, part-time, well-paid, world-improving jobs?

How can you let yourself enjoy a trail run, raft trip, or climbing adventure today when the future is unknowable, disaster may always strike, and more money = more security?

This is one reason I wrote Dirtbag Rich: because I hadn’t found a book that addressed all these questions in one place, especially as I navigated the polycrisis of my twenties. I ended up cobbling together practical advice and actionable philosophy from disparate sources, and eventually, decided to write the damn book myself.

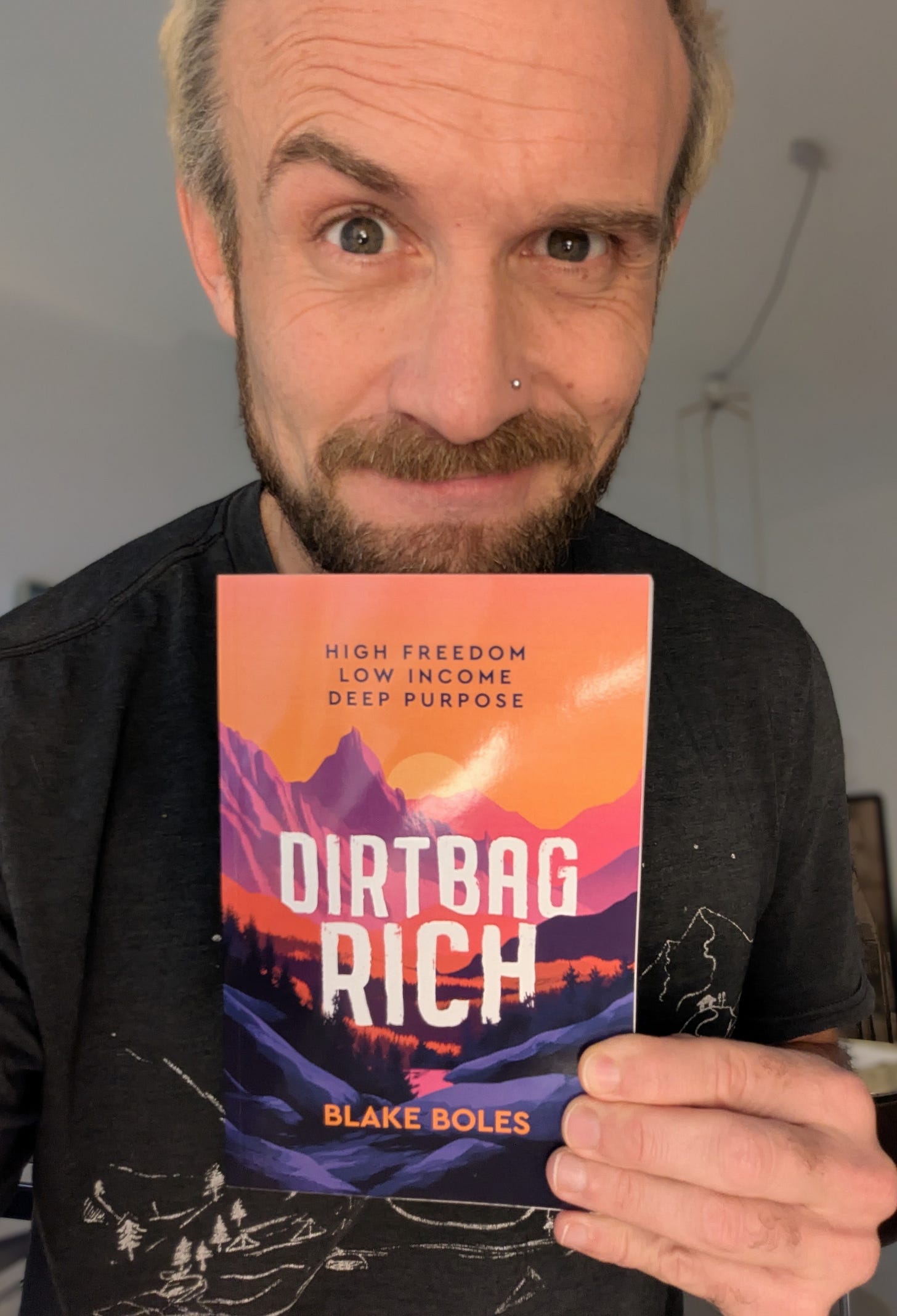

What you’ve found above are three of the 37 chapters of Dirtbag Rich, due for release in March 2026. Right now I’m printing test copies, reaching out to fellow writers for “blurbs” (those nice little paragraphs that authors write for each other), and awaiting the creation of some original illustrations.

I’m excited to share the final words with you in just a few short months.𖤓

For updates about Dirtbag Rich, stay tuned to this newsletter or the podcast.

“Progress party” is my catch-all term for societies that become freer, richer, more secure, and more inclusive over time. It’s not related to any actual political party.

Tim Mathis, author of The Dirtbag’s Guide to Life, first coined the term “dirtbag rich.” I interviewed him for the book, and he has generously supported my adoption of the phrase.

Thrilled to see that first proof copy in your hands — can't wait to see it out wandering the world!

It takes great effort of will to keep selling my soul. These worlds weaken my resolve. Wil have to keep the book locked somewhere