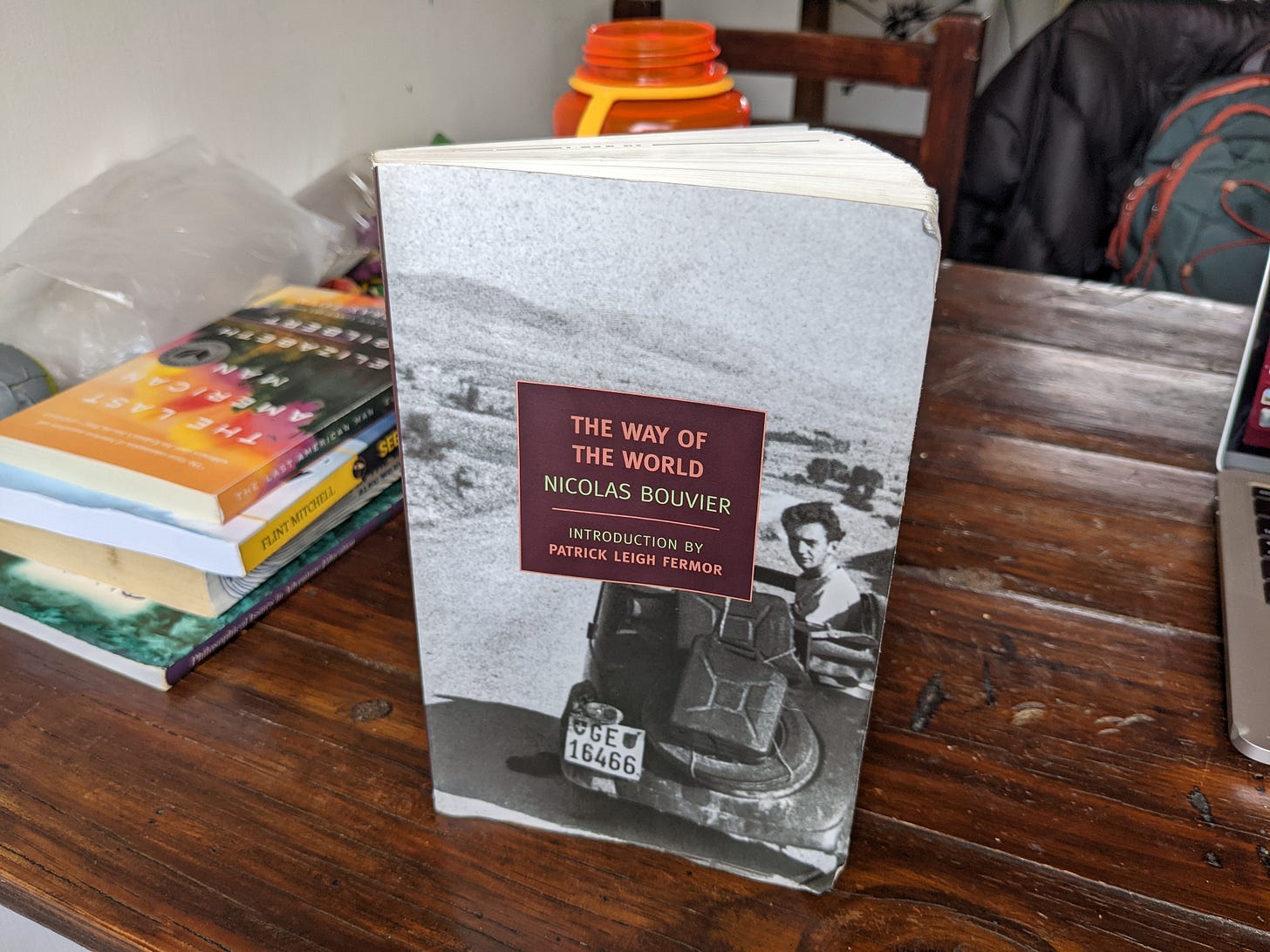

The Way of the World

lessons from two Swiss adventurers in the 1950s

In 1953, two Swiss men, just out of college, begin driving east from Belgrade. Their destination: Khyber Pass, Afghanistan.

In a journey that ultimately takes a year and a half, Nicolas Bouvier and his friend Thierry Vernet traverse Greece, Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan, working en route to fund their passage (Vernet as a painter, Bouvier as a freelance journalist & French teacher).

Their car, an aging Fiat convertible, breaks down repeatedly. The two young men serve as its primary mechanics, along with an ever-rotating cast of foreign mechanics.

A decade after the journey ended, Bouvier self-published his chronicle in French— L'Usage du monde—later translated and republished as The Way of the World.

The book is a first-order tale of adventure, with novelty, uncertainty, and emotion dripping from every page, as well as a meditation on the pleasures, terrors, and value of slow travel in foreign lands.

Most of the book is vivid prose, masterful storytelling, and cultural history—which you may sample here, here, here—but Bouvier’s philosophical musings are what interest me most. Below I share my favorite passages. Enjoy.

On the lure of travel:

Travelling outgrows its motives. It soon proves sufficient in itself. You think you are making a trip, but soon it is making you—or unmaking you.

When desire resists commonsense’s first objections, we look for reasons—and find that they’re no use. We really don’t know what to call this inner compulsion. Something grows, and loses its moorings, so that the day comes when, none too sure of ourselves, we nevertheless leave for good.

On coming and goings:

We left Serbia like two day-laborers, the season over, money in our pockets, memories full of new friendships. We had enough money for nine weeks. It was only a small amount, but plenty of time. We denied ourselves every luxury except one, that of being slow.

The nomadic life makes you sensitive to the seasons: you rely on them, even become part of the season itself, and each time they change, it seems you have to tear yourself away from a place where you have learned to live.

Loafing around in a new world is the most absorbing occupation.

On food and smells:

[It] was marvelous bread. At daybreak the smell from the ovens drifted across the snow to delight our noses; the smell of the round, red-hot Armenian loaves with sesame seeds; the heady smell of sandjak bread; the smell of lavash bread in fine wafers dotted with scorch-marks. Only a really old country rises to luxury in such ordinary things; you feel thirty generations and several dynasties lined up behind such bread.

Appetite was accompanied by emotional salivation, proving that food for the body and the spirit are closely allied in the sediment of travel: plans and grilled mutton, Turkish coffee and memories.

Then the clay and mud were lit up by a thousand fires and the autumn sun rose up over the six horizons still separating us from the sea. All the roads round the town were carpeted with willow leaves, smelling good, silently crushed by the teams of horses. Such expanses of land, pungent odors, the feeling that one’s best years lie ahead—they increase the pleasure of living, like making love.

On the mental and emotional benefits of travel:

The end of the day would be silent. We had spoken our fill while eating. Carried along on the hum of the motor and the countryside passing by, the journey itself flows through you and clears your head. Ideas one had held on to without any reason depart; others, however, are readjusted and settle like pebbles at the bottom of a stream. There's no need to interfere: the road does the work for you.

Travelling provides occasions for shaking oneself up but not, as people believe, freedom. Indeed it involves a kind of reduction: deprived of one’s usual setting, the customary routine stripped away like so much wrapping paper, the traveller finds himself reduced to more modest proportions—but also more open to curiosity, to intuition, to love at first sight.

Time passed in brewing tea, the odd remark, cigarettes, then dawn came up. The widening light caught the plumage of quails and partridges… and quickly I dropped into this wonderful moment to the bottom of my memory, like a sheet-anchor that one day I could draw up again. You stretch, pace to and fro feeling weightless, and the word ‘happiness’ seems too thin and limited to describe what has happened. In the end, the bedrock of existence is not made up of the family, or work, or what others say or think of you, but of moments like this when you are exalted by a transcendent power that is more serene than love. Life dispenses them parsimoniously; our feeble hearts could not stand more.

On cultural differences:

What’s to be done when nothing is available [in a country]? Frugality is one thing, and enhances life, but such continual poverty deadens it.

Needless to say the people here dreamed only of cars, water on tap, loudspeakers, consumer goods. In Turkey they point out such things, and you must learn to look at them with a new eye. The splendid wooden mosque—which you can find if you search—nobody would think of showing you, being less aware of what they have than of what they lack. They lack technology: we want to get out of the impasse into which too much technology has led us, our sensibilities saturated to the nth degree with Information and a Culture of distractions.1 We're counting on their formulae to revive us; they're counting on ours to live. Our paths cross without mutual understanding, and sometimes the traveller gets impatient, but there is a great deal of self-centredness in such impatience.

I believe that Americans have great respect for school in general, and for primary school in particular, the most democratic kind. I believe that of all the Rights of Man, the one that appeals to them most is the right to education. It’s natural in a country which is highly developed in civic terms and where other, more basic rights are taken for granted. School is one of the main ingredients of the American recipe for happiness, and so in the American imagination a country without a school must be the very image of a backward country. But recipes for happiness cannot be exported without adjustments, and in Iran the Americans had failed to adapt theirs to a context which puzzled them. That was the source of their difficulties. Because there are worse things than countries without schools: countries without justice, for instance, or without hope.

One can endure an isolated place, without supplies; if necessary, without safety or doctors, but I couldn’t stay for long in a place without the post.

Not sure how to categorize these quotes, but damn I love them:

Was my beard ‘existentialist’? What was ‘the absurd’? She had come across these words in a Tehran review. The beard was simply to make me look a bit older, as half my little class was in its forties. But the absurd? The absurd! In Switzerland I wouldn’t have been at a loss for a reply, but how could I explain what was quite beyond the life of Tabriz, a town which couldn’t be made to fit any philosophical system. Nothing was absurd here… but everywhere life was on the rampage, pushing up from underneath like a shadowy leviathan, forcing cries out of the depths, driving flies to plague open wounds, pushing out of the earth millions of anemones and wild tulips that within a few weeks would cover the hills with their fleeting beauty. And constantly drawing one in. It was impossible to remain aloof from the world, even if you wanted to be. Winter bellowed at you, spring soaked your heart, summer bombarded you with falling stars, the autumn vibrated in the harp-strings of the poplars, and its music left no one untouched. Faces lit up, dust flew away, blood ran; the sun turned the dark heart of the bazaar to honey, and the sound of the town—a web of secret connivances—would either galvanize or destroy you. But no one could escape it, and in this fatalism lay a sort of happiness.

We going up to bed when two timid knocks sound on the door. It was a Kuchi musician, with a tiny harmonium under his arm. He was one these wandering showmen who rove the subcontinent, a grey monkey on his shoulder, letting horses’ blood, casting spells, living off windfalls, theft or songs, avoiding temples and mosques in the belief that man is born to ‘wander, die, rot and be forgotten’.

On long-term vagabonding (which gives me hope for myself):

I don't know whether he got the nickname Dodo on the dig. His real name escapes me. He was a native of Grenoble, about forty years old, and had spent twenty of those on the road. Placid, a straight-faced comic, more detached than a Dervish and blending in with things all the better to observe them, he was very good company. Above all he had that phlegmatic nature which is no more than a form of the greatest resistance so necessary to a life of travel, where the over-excited and irascible always end up bashing into the image they've made of themselves. Dodo had lived everywhere for a while, left many jobs just as they became profitable, had learnt a lot and doubtless read a lot. He rarely talked about it all. He said 'voui' for oui on purpose, I imagine, and disguised his reading and his talents beneath a rather slow, rustic exterior for fear of his services being too much in demand: he liked to organize his own time.

A man in his forties would usually have become disenchanted with the life of a vagabond, and gloom would have set in. Time to draw a line. You travel, subsist and are seasoned; the years mount up; the pursuit loses sight of its goal and turns into flight; the adventure, emptied of its content, is prolonged by a series of expedients but loses all impetus. You perceive that travels may have a formative effect on youth, but they also make it pass. In short, you turn sour.

But not Dodo: he was completely at ease in his frugal, nomadic life. His soul had been scoured by his trials, his spirit remained fresh and ready for anything. Sometimes there was a mild nostalgia for white wine and walnuts and camembert... but no desire to go home or to settle down.

‘It’s not so much out of laziness,’ he would add, stretching out under the aspen to which he’d tethered his horse, ‘more out of curiosity—voui, curiosity.’ He sent smoke rings up into the sky, gradually drained of light.

On returning home:

When I went home, there were many people who had never left who told me that with a bit of imagination and concentration they travelled just as well, without lifting their backsides off their chairs. I quite believed them. They were strong people: I'm not. I need that physical displacement, which for me is pure bliss. Moreover, happily, the world reaches out to the weak and supports them.

That day [when the trip ended], I really believed that I had grasped something and that henceforth my life would be changed. But insights cannot be held for ever. Like water, the world ripples across you and for a while you take on its colours. Then it recedes, and leaves you face to face with the void you carry inside yourself, confronting that central inadequacy of soul which you must learn to rub shoulders with and to combat, and which, paradoxically, may be our surest impetus.

Finally, on flies:

For a long time I lived without hating anything much. Today, I positively hate flies. Even thinking about them brings tears to my eyes. A life entirely devoted to wiping them out seems to me a great destiny. I mean the flies of Asia; those who have never been out of Europe are no judges of the matter. In Europe flies keep to windows, to sticky liquids, to the shade of corridors. Sometimes they even wander on to a flower. They are no more than shadows of themselves, exorcised—that is to say, innocent. In Asia they are spoilt by the abundance of the dead and the abandon of the living, and they have a sinister insouciance. Tough and relentless, smuts from some horrible material, they are up with the sun and the world is theirs. Once it is daylight, sleep is impossible. At the slightest hint of repose, they take you for a dead horse and attack their favourite morsels: the corners of the lips, around the eyes, the eardrums. You find yourself asleep? They venture forth, get in a panic, and in their inimitable manner buzz up channels of the most sensitive mucus membranes in the nose, at which point you leap to your feet, retching. But if there is a cut, an ulcer or a spot that hasn't yet healed over, you could perhaps doze off for a bit because they will make a beeline for that, and their tipsy immobility then—replacing their odious agitation has to be seen to be believed. You can then observe one at leisure: it has no obvious appeal, is not exactly streamlined, and its broken, erratic, absurd flight, designed to get on one's nerves, is beneath contempt. The mosquito, which one would happily do without, is an artist by comparison. […and it goes on!]

Beware the information-saturation and “culture of distraction” of the 1950s! (What will they say about us in 2090?)

Ooooh, another book rec. Thanks. We are inspired by those who you share with us. Thanks.