The Last American Men

on Eustace Conway, Justin Alexander, and other modern pioneers and wanderers

In the late 19th century, telegraphs were connecting the coasts, passenger vessels were crossing the oceans, and maps no longer included blank spaces Where There be Dragons.

The American frontier had disappeared, and the entire world was becoming “civilized.” The proliferation of easy transportation (trains, cars, airplanes) bred nostalgia for journeys undertaken by foot, sailboat, and horse. Increasingly, the simple act of wandering off and removing oneself from society became difficult or impossible.1

During this time, “What will become of our boys?” became a powerful concern among parents, as Elizabeth Gilbert explains in her 2002 book, The Last American Man. It was also an uniquely American concern. In the European tradition, boys migrated from the country to the city to become refined gentlemen. In contrast,

The American boy came of age by leaving civilization and striking out toward the hills. There, he shed his cosmopolitan manners and became a robust and proficient man. Not a gentleman, mind you, but a man.

Gilbert’s book chronicles the life of Eustace Conway, one such young man who desperately wanted to strike out toward the hills to become a real man—and very much succeeded.

Conway became a famous wilderness survivalist in the 1990s for founding Turtle Island Preserve in western North Carolina, an environmental education center where he promoted a back-to-nature doctrine. He also achieved minor stardom for his amazing feats of outdoor endurance, such as riding a horse across the entire United States and speed-hiking the Appalachian Trail (wearing just two bandanas, and foraging almost all his food along the way).

Reading The Last American Man made me laugh out loud many times, not just because Gilbert is a terrific writer (she’s the author of Eat, Pray, Love) and Conway’s story is so fascinating, but because I already knew a very similar modern-day frontiersman: Jim Wiltens, the man who first inspired me to a life of adventure.

Like Eustace Conway, Jim Wiltens prided himself on feats of endurance in the wild—marooning himself on a deserted island of British Columbia to test his survival skills, crossing India’s Thar Desert on camelback—and spoke regularly about these adventures to school groups. Wiltens also created his own little utopian wilderness community where, like Conway, he promoted adventure, wilderness stewardship, and the virtues of “learning through experience, toughening up, showing bravery.”

Attending Deer Crossing Camp as an 11- to 15-year-old was deeply positive, but working for Jim Wiltens as a 20- to 25-year-old was where my real education began. Because just like Eustace Conway, Jim Wiltens was a Real American Man who prized asceticism, endurance, and hard work above all else.

Neither Turtle Island nor Deer Crossing was some barefoot hippy commune. Both Conway and Wiltens threw their entire beings into their little utopias, setting extremely high standards, demanding that others shared their insane work ethics, and alienating many along the way. “Most of the apprentices live in fear of Eustace,” Gilbert wrote about Turtle Island apprentices:

They talk about [Eustace] whenever he’s out of earshot—hushed and somewhat desperate conversations—huddled like courtiers trying to read the king’s motives and moods, passing on advice for survival, wondering who will be cast away next.

Possessing the necessary “talent for submission” was necessary to work for such men, and this was

especially hard for modern American kids who are raised in a culture that has taught them from infancy that their every desire is vital and sacred. . . The ‘What do you want, honey?’ culture has created the kids who are flocking to Eustace today. They undergo enormous shock when they quickly discover that he doesn’t give a shit what they want. And between 85 and 90 percent of them can’t handle that.

I was a product of the same self-esteem culture, and at age 20, I found myself magnetically attracted to Jim Wiltens as a figure who eschewed such coddling. Somehow I survived the experience and reaped the benefits of Wilten's mentorship and encouragement.2 Similarly, for those he deemed worthy, Eustace Conway was a powerful mentor and encourager. Gilbert chronicles the account of a young Turtle Island apprentice named Dave:

There is no way, Eustace said to Dave, that you can have a decent life as a man if you aren't awake and aware every moment. Show up for your own life, he said. Don't pass your days in a stupor, content to swallow whatever watery ideas modern society may bottle-feed you through the media, satisfied to slumber through life in an instant-gratification sugar coma. The most extraordinary gift you've been given is your own humanity, which is about consciousness, so honor that consciousness.

Revere your senses; don't degrade them with drugs, with depression, with willful oblivion. Try to notice something new every day, Eustace said. Pay attention to even the most modest of daily details. Even if you're not in the woods, be aware at all times. Notice what food tastes like; notice what the detergent aisle in the supermarket smells like and recognize what those hard chemical smells do to your senses; notice what bare feet feel like; pay attention every day to the vital insights that mindfulness can bring. And take care of all things, of every single thing there is in your body, your intellect, your spirit, your neighbors, and this planet. Don't pollute your soul with apathy or spoil your health with junk food any more than you would deliberately contaminate a clean river with industrial sludge. You can never become a real man if you have a careless and destructive attitude, Eustace said, but maturity will follow mindfulness even as day follows night.

Where else can a middle-class suburban youngster to find such moral guidance, without the baggage of religion? This, I believe, is why modern male-advice-givers like Jordan Peterson find large audiences, and why wilderness and challenge-oriented programs will always have a market.

What will become of our boys? The question makes me think of Christopher McCandless, the subject of Jon Krakauer’s book Into the Wild, about which I’ve previously written. If McCandless had channeled his boundless energy, intellect, and thirst for adventure in a more prosocial direction—like founding a wilderness preserve or children’s summer camp—might he not have wandered so far off-grid and ended up dead?

I want to believe this. But another book about another Real American Man gives me pause.

Jason Alexander (born Jason Shetler) was a soul-seeking traveler who roamed the world for years, achieved minor Instagram stardom, and intended to continue traveling for a long time—until 2016, when he ventured into a remote valley in India at age 35 and never returned. Alexander’s story was then chronicled by journalist Harley Rustad in 2018 and expanded into a 2022 book, Lost in the Valley of Death. (Here’s a good summary.)

Jason Alexander was good-looking, charismatic, and curious. Fit, healthy, and seldom sick. Positive, competent, and seemingly able to accomplish anything he set his mind to. A white dude raised in suburban comfort. Like the other Last American Men we’ve discussed, Alexander was very much born on third base, which allowed him to take bigger risks, push further into the unknown, and boldly experiment with life.

Alexander’s family split when he was 11, and he was stressed by constantly moving between new homes. Never enjoying traditional school, his parents enrolled Alexander in the highly alternative Wilderness Awareness School for his junior and senior years, where he mentored under the famed naturalist Jon Young, the protégé of a yet-more famous naturalist, Tom Brown, Jr.3 He soaked up wilderness survival skills like a sponge and soon began teaching them at the Tracker School in New Jersey. He began taking bolder risks, like scaling bridges and buildings, diving from cliffs, and living in the wild with minimal supplies, and started describing himself as a “ninja of sorts.”

Like Conway and Wiltens, Alexander was a passionate consumer of adventure narratives. His favorite books include Siddhartha, Vagabonding, and even Into the Wild. He never went to college, opting instead to start a punk band in the San Francisco Bay Area and mentor youth at the nearby Riekes Center. He then pivoted to a 3-year stint as a well-paid sales representative in Miami, allowing him to travel the world in high style. But then, like Siddhartha, he dramatically renounced his materialistic life with words that I (or any other millennial soul-seeker) could have penned:

I am running from a life that isn’t authentic; that isn’t me. From the numbness that accompanies a sterile life of luxury. I’m running away from monotony and towards novelty; towards wonder, awe, and the things that make me feel vibrantly alive.

He threw himself into hardcore international travel in his late twenties and early thirties, exploring ever-more remote destinations and connecting with younger travelers to preserve his own youthful mentality. He began making ever-more questionable decisions— buying and selling hash, dedicating himself to a sadhu (religious guru), and doing 14 consecutive Ayahuasca ceremonies. He openly questioned if he’d live past 40, and whether he’d ever find fulfillment with a job, long-term relationship, or children. Like McCandless, he barely spoke about his parents, and he stopped using his birth name. “He was terrified of losing his freedom,” an ex-girlfriend said; “The only picture he painted for himself was to travel the world for the rest of his life.”

The final fate that befell Jason Alexander is still a bit of a mystery. What seems clear is that he got involved with the wrong people in a remote part of India. In the end, his story paralleled that of Chris McCandless and Everett Ruess (another wanderer described in Into the Wild): he was a promising young man who pushed himself too far in the search for wilderness transcendence.4

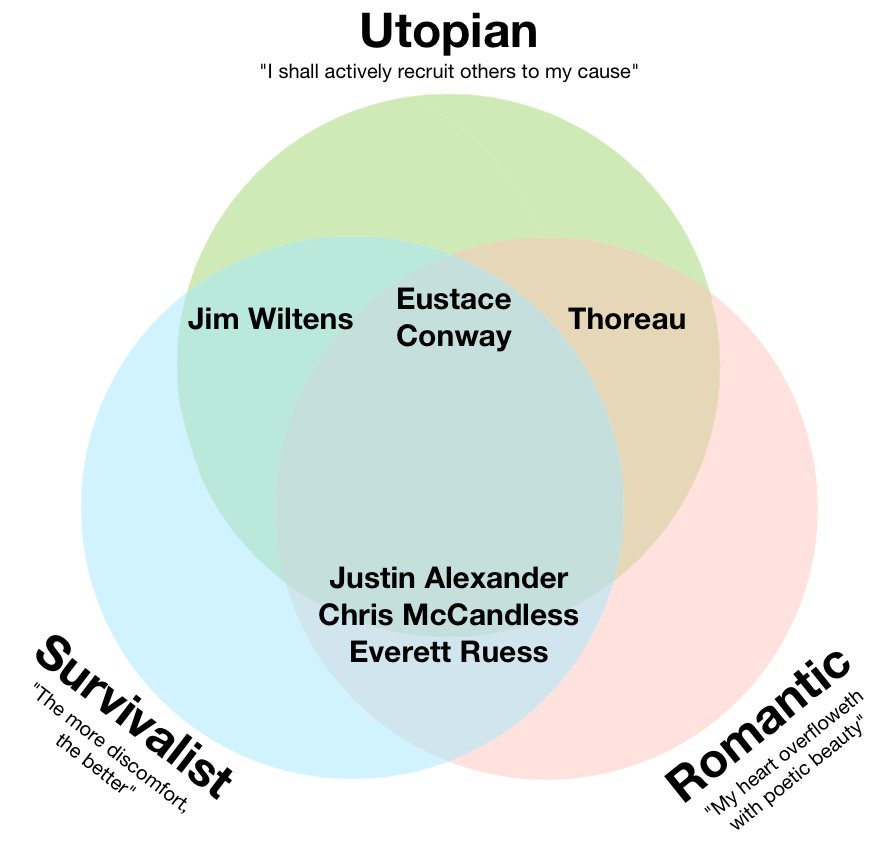

Like other Last American Men, Alexander felt deeply called to evangelize about his lifestyle. He wanted to show the world a more sane and sustainable way of living, one that involved wilderness immersion, constant exploration, minimal consumption, and the never-ending pursuit of “simplicity.” With sufficient reconnection to nature, the Last American Men believed that societal ills could be remedied: overconsumption, disconnection, disillusionment, hubris. Each harbored strong beliefs about how to live one’s life morally in an amoral world, despite their rejection of modern religion. (If all these men share one intellectual forefather, it would undoubtedly be Henry David Thoreau.5)

Near the end of Lost in the Valley of Death, the author shares a powerfully accurate summary of Justin Alexander’s situation, one that could equally be applied to all the other Last American Men (and myself):

Justin was born into a certain degree of privilege, afforded opportunities because of class, race, and gender that allowed him a foundation often taken for granted: freedom. It was a state he sought yet in many ways had had all along. With enough money, something he was always adept at finding, he could go anywhere. Yet as much as he was seeking, he was also running—from relationships, from growing old, from responsibility, from mundanity. Perhaps his inherent privilege was the root of his constant feeling of dissatisfaction: to achieve what he sought, many times he shed his life, abandoned what he had built, pared his possessions back to what was necessary, and started anew.

The Last American Men don’t need our pity, but they deserve our understanding.

The ceaseless globalization of society, the closing of every frontier, and the fetishization of security seems to uniquely disrupt a subset of able-bodied, independent-minded young men. Despite their privilege, they find themselves unable to fit into society, driven by a lusty need to push themselves to the edge—to create their own frontiers, and then cross them.

As Eustace Conway wrote in his journal at age 22:

I need something new, fresh, alive, stimulating. I need life, close-up, tooth and claw. Alive, real, power, exertion. There are more real, fulfilling and satisfying things to do than sitting around talking to a bunch of good old boys about the same old things, year after year. I don’t want to talk about doing things, I want to be doing things, and I want to know the realities and limits of life by their measure! I don’t want my life to be nothing, to not make a difference. And people tell me all the time how I am doing so much, but I don’t feel I’m even scratching the surface. Hell no, I’m not! And life is so short, I could be gone tomorrow. . . . How to do it? What to do? Can I? Where do I go? Escape isn’t the answer. There is only one way—destiny, destiny. To trust destiny.

How do we, as a society, give an outlet to this kind of energy? How do we keep it from becoming self-destructive? How do we offer young people a genuine sense of risk and adventure in a world that feels ever more safe and predictable?

Eustace Conway and Jim Wiltens channeled their youthful enthusiasm into experiential education and wilderness advocacy. They saved themselves by looking outside themselves.

Jason Alexander’s story is mixed. He did look outside himself by mentoring young people and promoting his values through Instagram. Unlike McCandless, he himself received strong mentorship as a young person, and enjoyed a wide network of friends. But like McCandless, he ultimately sought his answers in wilder and more remote places, costing him his life.

What if Conway or Wiltens had died while pursuing one of their youthful, more extreme adventures? What if Alexander or McCandless were a bit luckier? All the stories might have been flipped.

Wherever this uniquely American, uniquely masculine drive comes from, I believe it’s here to stay. We’ll be hearing these stories for a long time.

For an excellent, brief history of these generational shifts, see The Fascination with the Impossible by Sylvain Venayre.

Most Deer Crossing instructors never returned for a second season because working for Jim Wiltens was incredibly hard work. But some, like me, survived and returned, over and over again. Why? Gilbert suggests that a certain “interesting species” of coddled youth actually thrive in such environments:

They don’t talk a lot, and they don’t seek praise, but they seem confident of themselves. They are able to make themselves vessels of learning without drowning in it. It’s as if they decide, when they come here, to take their fragile and sensitive self-identity, fold it up tight, tuck it away someplace safe, and promise to retrieve it two years later, when the apprenticeship will be over.

After a four-day vision quest in his late teens, Tom Brown Jr. felt compelled to pursue “a pure reality filled with excitement, adventure, and intensity—a life of rapture rather than a life of comfort, security, and boredom like everyone else was choosing.” Sound familiar?

Lost in the Valley of Death reveals a few significant confounding factors in Justin’s life story, such as a traumatic car accident at age 18 and a few episodes of sexual assault.